Wuhan's a gift to social media's critics

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis couldn't have asked for better timing.

You’re reading Slow Build, a biweekly newsletter on tech & society by Nancy Scola.

So let’s talk today about Floooooorida. Also Wuhan, China. Then back to Florida again.

On Monday, Florida’s Republican governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill meant to make it more difficult for Facebook, Twitter, and other big online platforms to restrict what conservatives — including current Palm Beach resident Donald Trump — have to say on those sites. That the bill, as drafted, is of serious constitutional questionability and in conflict with existing federal communications law provides a perfect opportunity to have a poke at the state, and Republicans more broadly, for again whiffing in the right’s attempt to challenge what they see as Silicon Valley’s reflexive dislike of them.

But let’s back up for just a wee bit to understand what’s actually in this Florida bill, the full text of which is here.

The new law takes a three-pronged approach.

Under it, Floridians can sue the online platforms for monetary damages when they’ve been treated unfairly under the sites rules, while requiring the companies to state exactly what those rules are — what the governor’s office called an attempt to avoid the companies “moving the goalposts.” The new measure also empowers the state AG to go after companies who engage in deception as they go about enforcing their standards, and then prevents violative companies from contracting with government. Finally, it tells Florida’s elections commission to penalize companies at a rate of $250,000 a day for “deplatforming candidates” for statewide office; there’s a lesser fine for non-statewide candidates.

But as much as it pains me to say it, what’s in the Florida bill isn’t the point.

Why the details aren’t all that relevant is case is captured well in the current situation having to do with Wuhan, China, and the controversy over whether the novel coronavirus actually emerged not from a wet market there but from the Wuhan Institute of Virology — a controversy that could not have come in a better shape or at a better time for DeSantis et al.

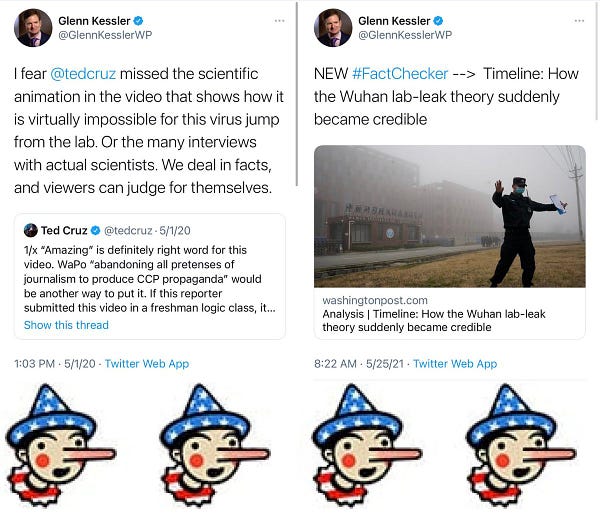

Over on Slow Boring, Matt Yglesias has a great and valuable rundown of the situation, but the short version is a theory of the pandemic’s root cause that was largely laughed at when it came out of the mouths of people like Arkansas Republican Senator Tom Cotton has, as the Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler — known at the Post as The Fact Checker — put it yesterday, “gained new credence.”

The whole Wuhan mess — which Yglesias fits into a context of "how egregious it was to lean so heavily into the Tom Cotton Is Wrong narrative" — has almost everything when it comes to conservatives’ charge against both the media and Silicon Valley, including their complaint that know-nothing reporters1 assume that if it comes out of the mouths of Republicans, it’s suspect. (This newsletter’s too short to go into why that approach has gained traction over the last five years. But let’s say it saved a lot of time.)

What’s more, platforms like Facebook and Twitter blithely outsource at least some of their fact checking to this same crew.

All of which makes this tweet by Ted Cruz — one of the loudest voices in the anti-platform right — entirely predictable:

A fairly simple idea has gained enormous traction on the right: the media holds conservatives in contempt.

And what’s more, Facebook and Twitter are the media on steroids.

Of course, the platforms insist they’re not biased against conservative voices, and tech advocates say the changes called for by folks like DeSantis would break the Internet and lead to less diversity of ideas online. But those are fairly dry arguments when stacked up against the idea, as DeSantis put it in signing the social media bill into law this week, “we the people are standing up to tech totalitarianism.”

Do savvy, ambitious Republicans politicians like DeSantis know that this is an enormously juicy political issue for them? Yes, of course. Ron DeSantis has considered the political implications of his actions.

But do conservatives also believe what they’re saying about Silicon Valley? I haven’t seen anything telling me they don’t.

So, with it hardened into wisdom on the right that ‘the media’ and Facebook and Twitter treat them unfairly — a word, “unfairly,” that’s right in the bill, right next to mention of the platforms “not acting in good faith” — the only question becomes what to do about it.

And what we’re witnessing when it comes to Republicans and Silicon Valley is the former iterating about what to do about the later. To put it more plainly, they’re just trying stuff out, seeing what sticks.

It almost goes without saying that the DeSantis bill is a direct descendent of the social-media-targeting executive order that Trump signed near the tail end of his time in office, almost immediately after his Twitter account was taken away. In fact, the bit about punishing bad-acting platforms by restricting their ability to do business with government was one of the main provisions of Trump’s order. The EO didn’t go much of anywhere. Even people in the White House at the time said they didn’t really get the mechanisms by which it was supposed to create change.

But that was by no means a fatal flaw. It was right in spirit, and it was a first shot. Trump took his. DeSantis has lined up to take the next.

If it misses, eh. On to the next attempt. They’ll try federally. They’ll try in Florida. That’s how these things work.

One other aspect of the bill that has come in for particular derision is worth fixating on for a moment — one exempting from the law’s punishments any “company that owns and operates a theme park or entertainment complex.” That get-out-of-jail card is obviously targeted at Disney, and seems a way of protecting in particular its Disney+ platform.

It’s almost funny, and so perfectly Florida. But this isn’t even the first time that laws with big implications for tech have been crafted to suit Disney.

In fact, U.S. copyright law — which among other things, shapes what we can share on platforms like Twitter and Facebook — is what it is because of Disney. Here's Josh H. Escovedo of the firm Weintraub Tobin explaining some years back. It’s important context so we’ll let him go on at some length:

“If you’ve ever applied for, or researched copyright law, you likely learned one thing above all else: it’s not a perpetual right. So, how, you might wonder, have companies like The Walt Disney Company managed to maintain copyrights on certain creations for almost 100 years? In the case of the Walt Disney Company, the answer is simple. It is powerful enough that it actually changed United States copyright law before its rights were going to expire.”

In 1928, Walt Disney released the first Mickey Mouse cartoon: Steamboat Willie. At that point, the work was entitled to protection for 56 years (28 years for the initial term and the 28-year extension). Under the Copyright Act at the time, the copyright on Mickey Mouse should have expired in 1984. But before Disney’s mascot could be pushed into the public domain by operation of law, Disney embarked on a serious lobbying mission to get Congress to change the Copyright Act.

Disney’s lobbying paid off in 1976 when Congress passed legislation which changes the copyright scheme such that individual authors were granted protection for their life, plus an additional 50 years, and for works authored by a corporation, the legislation granted a retroactive extension for works published before the new system took effect. The result was that the maximum term for already-published works was extended from 56 years to 75 years, thereby extending Mickey Mouse’s protection out to 2003.

And it doesn’t stop there. In 1998, Congress passed the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act that had the effect of pushing the Mickey Mouse copyright to 2023.

The point? Public policy often isn’t a one-and-done type of thing, and that it might be narrowly targeted to meet the needs of a limited set of interests — Disney, Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis — doesn’t also mean it won’t become law. Recall that changing communications law government the Internet to address online sex trafficking after years of trying was impossible nearly up to the minute it wasn’t any more.

That Ron DeSantis and others of like mind are suddenly going to drop the issue just because this one particular law might not live for very long seems a bad bet, especially when you have DeSantis tweeting sentiments like this:

The thing to notice there from DeSantis (other than the thumbs-up; choices were made):

"This is just the beginning."

There's very little reason to think that's not the case.

Other stuff of current interest:

—Twitter’s offices in India got a visit from police after it labeled a political tweet, reports Variety’s Naman Ramachandran:

The ongoing battle between the Indian government and Twitter intensified on Monday with the Delhi Police raiding the social media outfit’s Delhi and Gurgaon offices over a tweet marked by the platform as “manipulated.”

The tweet in question originated from Sambit Patra, national spokesperson of India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), on May 18. It detailed the efforts of the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress, in supposedly helping the needy during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that is currently ravaging India, and disparaging the BJP’s efforts.

(Recall that the party in question, the BJP, was featured in our discussion two weeks back on “the hard and true limits of fact checking.”)

—Over on the American Prospect, David Dayen details the intrigue over who’ll head the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office next, and the role of Connecticut Democratic Senator Chris Coons in the pick:

Patents have not historically animated sustained intraparty fights that spill out into headlines. But Coons’s pro-IP, pro-patent stance, and his long friendship with the president, has elevated the issue, and turned the selection of the next director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) into a flashpoint. Coons has been aggressive in working with the White House to secure a director who shares his viewpoints, and his top candidates have represented patent owners as lawyers or trade group leaders. According to sources on Capitol Hill and from outside groups, Coons has claimed that he was granted the power to make the USPTO choice in exchange for staying in the Senate. Coons had been seen as a potential pick for secretary of state.

—And the civic tech world’s Waldo Jaquith spotlights a new report from GSA’s 18F branch on the feasibility of U.S. courts upgrading their case management system, including PACER:

The full report’s here.

Finally, and about this I’m not proud: