“The entire U.S. is built on algorithmic governance”

A Q&A with Colgate’s Dan Bouk on the hidden formula binding Congress

Hi there, and welcome to the May 7th edition of Slow Build, a newsletter on tech and society by yours truly, Nancy Scola. We made it to Friday.

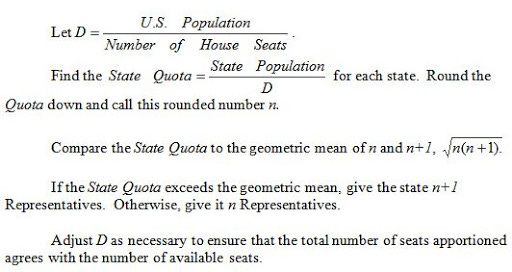

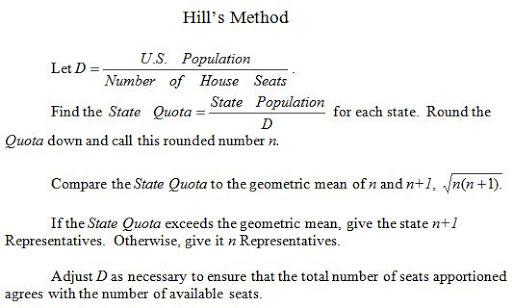

A key driving ambition of Slow Build is to take the time to dig into the obscure ways technology and data are shaping what it means to be human. To that end, this week we have a Q&A with Dan Bouk, an associate professor of history at Colgate University and a fellow at Data & Society who has been doing fascinating work on the U.S. census. In particular, Dan’s illuminating the algorithm Congress has used almost exclusively since 1929 to figure out which states get how many seats in the House of Representatives, called the Huntington-Hill method. And those hidden calculations have enormous impact on the distribution of political power in the United States.

(The normal Q&A caveats of this being edited and condensed apply.)

Not subscribed to Slow Build yet? Please do!

A Q&A with Dan Bouk

Scola: The reason I’m so intrigued by your work is that we obsess over the apportionment of seats in Congress but spend so little time thinking about the process by which we come up with the number of seats in the House and how, exactly, they should be divvied up in the first place. You seem to be arguing that we should instead be focused upstream. Why are we looking at the wrong things?

Bouk: It's not so much that we're looking at the wrong thing but that we end up fighting a lot within constraint arguments that needn't be so constrained.

So when the furor about New York came out, saying ‘New York loses a seat by 89 people,’ when it's that close, when your margins are that close, when such a tiny difference can cause a pretty big shift in politics, and when we're looking at a census that just ran in the middle of a pandemic and it produces a number that appears to be precise to the one digit — like, no one should actually believe that number really means what it means, but we use those numbers as if they're exactly precise to make this precise calculation. That's where I start to think, well, maybe we shouldn't then use it to govern a zero-sum game, in which some states could lose big as a result, when we have an alternative, which is to choose to make it so that no states lose.

Let’s back up. The way things work now, we hand out the first 50 seats to the states, and then go down the line figuring out who has population enough to qualify them for additional seats, right?

The Constitution guarantees each state one seat, and then from on out, you divide the population total by an estimate of how big each House district should be. And then you divide each state total by that, and it usually produces a fraction like, “and three-tenths of a representative, or “seven-tenths of a representative.” Depending on how do the calculation, it will change that fraction a little bit, and depending on how you set that number to divide it by, it’ll change that.

And then you have to pick a rule to decide, of those fractions, which ones deserve to go up, which ones deserve to go down? And it's really not simple, because if you've said ahead of time there’s only gonna be 435 seats, you have to keep nudging and adjusting all of those different variables to make it so that it actually adds up to 435 once you’re done.

And the smaller the integer number, the geometric mean is going to be closer to the lower integer than to the halfway point. So the result is, if you use that as your measure for where the fractions tip over, smaller population states are more likely to get that next seat than bigger population states are by just the tiniest of fractions.

The older method that was used right before, called the “method of major fractions,” [also called the Webster method] literally just used that halfway mark. The result is this in this last apportionment meant based on the numbers that the Census Bureau has released, Ohio and New York would have gotten the last two seats at 435. And Montana and Rhode Island would have lost those seats.

But for me the historical lodestar in terms of what used to happen was, more often than not, the House would grow to such a size that no state would lose a seat. And in that scenario, this year, you'd have to increase by 19 seats for the seven losers [that is, the states that lost seats in this apportionment] to keep their seats. But in the middle, other states are also gaining because they’re in line before the states that are losing.

And so the solution in your mind is doing just that — growing the size of the House, not using one of the other possible models?

I like the other models, because at least put some attention on it and I think it would be a tiny improvement — like, I think major fractions is better than equal proportions because it would make every-so-slightly an improvement for people in large states who are now at disadvantage.

You’ll find political scientists talking about the Wyoming rule, which is a formula for figuring out how big the House should be based on the smallest district, or the cube root law. But this comes down to politics, and I like democracy more than I like hard-and-fast rules. So I’d rather put it in the hands of Congress to figure this out. And I have confidence that Congress can actually apportion itself if it’s not a zero-sum game. I have zero confidence that Congress can apportion itself if it is a zero-sum game.

Pulling back a bit, why is framing this as an algorithm the way you do useful?

Part of the reason I got interested in this is that I think we live in a society that has a lot of situations in which people don't trust politics or democracy or government, and instead want to put a mechanical system in control. And I think often we've learned that doesn't actually turn out well for democracy. It’s only exacerbated now where people are starting to talk about these kinds of dreams of putting intelligent systems and AIs in charge of making rules.

Part of my motivation is to think about how and why we start to have these ideas that it's better to remove these difficult problems from democratic governance, and instead substitute for them some kind of an automated system.

Do you draw any connections between this work and the current debates over algorithms in social media?

So the other reason I like to frame it this way is I don't think we're served well, often, by the language of the newness of algorithmic governance. I think it's really important to understand we've been dealing with this at least a hundred years.

I mean, the entire United States is built on algorithmic governance, because that's what the apportionment works on. People in Congress can deal with this stuff. They are, in fact, they're constantly dealing with these issue. And I feel like tech companies especially love to obfuscate by making it seem newer and more complicated and more sophisticated than it actually is.

Yeah, an argument the tech companies have been making on Capitol Hill for years is that Congress can’t possibly understand what it is they do…

Which is what the experts said back in the 1920s to Congress. And probably most congresspeople can't really understand it, exactly — and yet they can still make perfectly reasonable judgments because they can see what the effects are.

Read Dan’s report, “House Arrest: How An Automated Algorithm Constrained Congress for a Century,” here.

***

By the way, if you haven’t gotten a chance to watch “Coded Bias” yet, it’s worth doing. It delves into the assumptions baked in to the algorithms governing everything from facial recognition to who gets loans at what rates. Now, I don’t think we’ve yet mastered making good art about modern tech. There’s far too many scenes of robots pulling our strings like puppets. And please for the love no more clips from “Minority Report.” But at the very least it will put you on notice to look for the role algorithms are playing in our daily lives, and that’s the first step.

***

About that Facebook decision…

The Facebook Oversight Board, you might have heard, upheld Facebook’s decision to temporarily ban former President Trump, but they weren’t happy about it. The group signed off on the decision while ‘insisting’ that Facebook revisit it in six months. Here’s the rub, though. It’s not at all clear that the board has the power to insist Facebook do anything of the sort. Of course, there’s the PR aspect here, where Facebook’s eager to validate the board and its moderating effect, in part because it makes Facebook ’s life inordinately easier.

But from everything I can figure, the company’s under no obligation to actually take up the decision again. So the company may well check back in come November and say, “Nope, everything still looks good,” and move on with things. Does that make the oversight board less effective? No, I don’t think so. Long-drawn-out resolutions are part of our formal justice system, too. And it may well be that this is the best-case scenario for everyone involved for the next half-year, at least. Come November — well, who the heck knows where we’ll be come November. Trump’s new social network could be up and running by then.

Further reading: Back in 2014 while working at the Washington Post, I did a Q&A with Columbia law school professor Eben Moglen about Facebook. I think it’s still useful in putting this week’s Facebook decision in context, including why it’s so difficult for us to just walk away from Facebook once and for all. The short version: we like spying on people.

Finally…Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer was on Ezra Klein’s podcast, and in a quick aside he said something I thought was extremely revealing about why we shouldn’t hold our breath on Congress changing the law governing how online platforms handle content:

Thanks for reading, and see you next week.