Busy week! Let’s do a roundup.

Facebook is going to be doing away with some of the special treatment it’s long given to politicians, reports the New York Time’s Mike Isaac:

Facebook plans to announce on Friday that it will no longer keep posts by politicians up on its site by default if their speech breaks its rules, said two people with knowledge of the company’s plans, reversing how it has allowed posts from political figures to remain untouched on the social network.

The change, which is tied to Facebook’s decision to bar former President Donald J. Trump from its site, is a retreat from a policy introduced less than two years ago, when the company said speech from politicians was newsworthy and should not be policed.

—It’s a huge move, especially given Facebook VP Nick Clegg’s insistence that it’s not right for Facebook to “prevent a politician’s speech from reaching its audience.” But it’s also probably an inevitable one. In truth, the policy was always a bit of an inconsistent mess, and even people inside Facebook had trouble explaining it.

—The thing is, losing that sort of social media edge can be a real ding for a politician, as Donald Trump’s finding out. The former president’s blog made it all of 29 days, with Trump reportedly not pleased that it wasn’t getting the same sort of traction his tweets and Facebook posts did before he was banned from both platforms — proof to some he can’t compete on a level online playing field.

—In some ways, we’re seeing the social platforms abandon an early idea: that politicians were their allies and VIP users. Whether because of free speech or the hope of currying favor, the assumption was that they should be treated well. The thinking for a long time was that politicians would need to be protected from abuse, not that they would be the ones instigating it. As someone close to Twitter in those early days told me with a laugh, when you talked about politicians back then it was “as the victim, not the perpetrator”:

“There were certain assumptions that the President of the United States was not someone you had to worry about. It seems so naive in hindsight.”

—But you can offer politicians your hopes and prayers for getting through this difficult time:

The company says it’s meant in part to help “faith and spirituality communities” that have struggled to meet in person because of COVID.

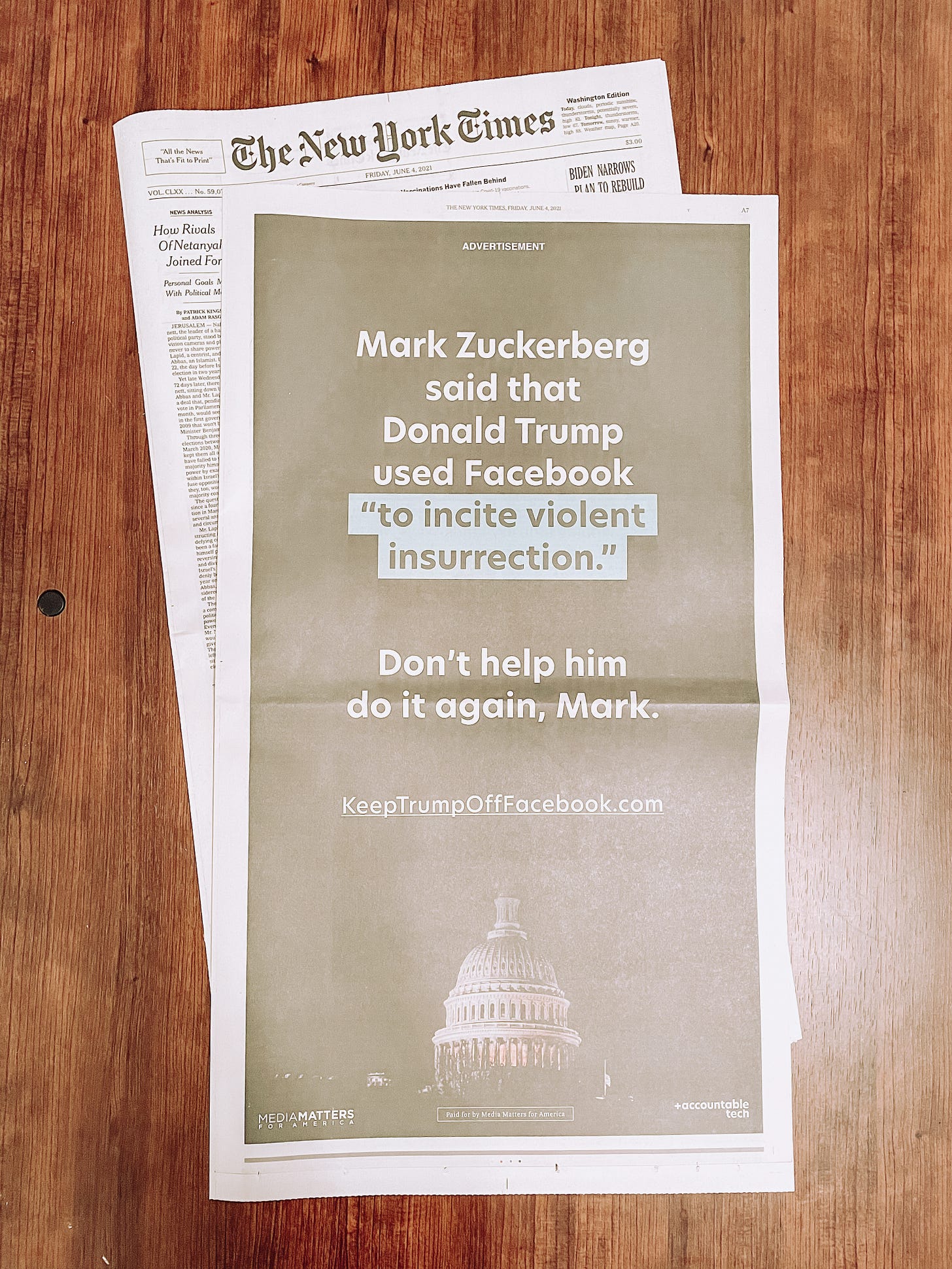

This new ad from the groups Accountable Tech and Media Matters is greeting readers of the print New York Times today:

Instagram says it’s going to tweak its algorithm to promote reposted content in its “stories” the same as as it does original material, in response to complaints that it was giving short shrift to the resharing of pro-Palestinian posts.

—Giving parity to reposted posts is an interesting decision for the Instagram, given that since going back to the days of its original founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, it’s balked at encouraging users to reshare posts, as it was supposed to be a platform for creativity. (That was one way, its founders thought, it wasn’t Facebook.) But resharing happens to be how a lot of Instagram users right now are expressing a stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The risk for the company: that political resharing turns Instagram into just another cacophonous social network.

Ev Williams is trying to reset Medium, again, and some inside the company aren’t happy, especially after he issued what’s come to be known as the ‘culture memo.’

Analysts and designers from the U.S. Digital Service and the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs scrambled to simplify the declaration form Americans have to use to get the protections of the CDC’s eviction moratorium —trying out more than 20 versions over two weeks before landing on one meant to be dead-simple:

The idea that because we’re all increasingly living our lives online our digital records wouldn’t be held against out is playing out as just about the opposite, says Kashmir Hill for the New York Times: “It almost makes you forget that it wasn’t supposed to be this way.”

And the New Yorker’s Charles Duhigg profiles Chamath Palihapitiya, looking at how his narratives of “heroic capitalism” have carried his from his days as Facebook’s head of growth to now serving as the “Pied Piper of SPACs.” One delicious bit is Duhigg’s retelling of Palihapitiya telling off a mutual-fund manager at a meeting of would-be investors:

“People either love Chamath or they hate him, and that’s fantastic, because polarization gets attention,” the attendee said. “Polarization gets you on CNBC, it gets you Twitter followers, it gets you a megaphone. If you believe that Chamath can get an hour on CNBC to explain Virgin Galactic, then you want to buy into this deal, because attention is money.” Having a great story, and knowing how to tell it, can be a quick way to get rich. Which is exactly how capitalism, at certain moments, is supposed to work.

Funny story: I interviewed Palihapitiya via Zoom for a possible profile a few months into the pandemic, and the room behind him was so breathtaking that my first thought was that the backdrop was fake. He called it his “his little Zen hideaway from four kids, just north of Palo Alto.”