Crypto people are making the Internet weird again

The marriage of collective action and millions of dollars raises all sorts of fascinating questions.

Happy Friday, folks. A reminder that you’re reading Slow Build, a newsletter on tech & society. Thanks for doing that!

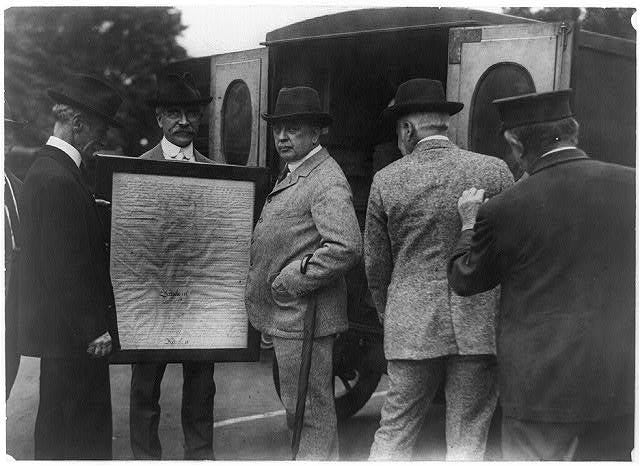

You might have heard that an ad hoc group of crypto aficionados came together this week in a bid to collectively buy a copy of the U.S. Constitution, one of only two privately owned first-printings of the 13 known to be in existence. They raised more than $40 million to participate in Sotheby’s auction, organized mostly through Twitter and Discord, but in the end, last night, didn’t win. The push, called ConstitutionDAO, for “decentralized autonomous organization,” was, like so much in cryptoland, a goofy joke and also pretty serious. (See dogecoin.)

“There was no way to distribute a document of [the Constitution’s] size… Without this printing, we wouldn’t have had a nation.”

— Selby Kiffer, Sotheby’s senior vice president for books and manuscripts

Even if it is tempting to write the whole thing off as a stunt, there’s still a lot to learn from it about the future of this whole Web3 business in particular and the future of collective action in general.

It’s raising questions like, what does ownership really mean in a situation like this? If ConstitutionDAO had made it, participants would have gotten an “governance token” that gave them a voting stake in how to actually steward a foundational national document once you’ve, you know, bought the thing. Is that what people thought they were buying? In that vein, partly over concerns that investors might take over the group with nefarious intentions, a “core team” of a dozen people was created to sign-off on final decisionmaking? As is likely obvious, that’s a bit of a curtailing of the whole spirit of a truly horizontal group.

And what happens if an “Anti-ConstitutionDAO” were to pop up, a group that actually did want to buy the document and, well, destroy it? Of course, an individual could do that, too. But there’s much less incentive for one person to spend tens of millions on that effort than there is for lots of people to spend ten bucks on it, on a lark. And now, there’s questions about what happens to the money pledged here. It’s refundable, but not automatically refunded. So this morphs into a fund where the reason for being is…a shared love of the United States’ founding documents?

Not that any of those questions necessarily point to flaws in the model, but they’re fascinating things to watch get answered. The quality of the responses will help determine whether this next phase of the Internet is able to recapture some of the whole collective-action vibe that in theory at least marked Web 2.0 and 1.0 before it.

It also echoes some of the same leaderless — or at least, less leader-y — actions we’ve seen around Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter.

Except! In this case, it’s backed with a great deal of money.

Given the way the world works, that seems a crucial distinction. The ability to marshal those resources gives instant entry to the world’s establishment institutions. Take Sotheby’s. The chat on the 277-year-old auction house’s YouTube feed for last night’s auction was an endless stream of “gm” and “wagmi” and “frens” and other crypto patois.

Meaning, back here in official Washington, people are scrambling to figure out the tax implications of cryptocurrency, an early battle over just how far down the crypto stack their regulatory reach goes. The coming weeks and months we’re likely going to see Washington trying to come to grips, too, with the sort of organizing and other changes that crypto might bring.

And that comes as the politics of crypto in D.C. are still enormously unsettled. Democrats especially are unsure whether the whole thing is a tool for bypassing intermediaries who exploit those who lack power or a tech-world scam dressed up in talk of “decentralization” and “democratization.” Buckle up.

—By the way, you can actually watch the auction itself, at two hours and 22 minutes in. It starts with an introductory video featuring from Sotheby’s Selby Kiffer, senior vice president for books and manuscripts, who shares this gem about pre-Internet life in these United States:

“Even though the nation was much smaller than it is today, it was still a lot of people, and there was no way to distribute a document of this size. This had to be printed, via the Continental Congress.

And this is what people in New York, people in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Rhode Island, Delaware read when they called their own conventions within their state to say, ‘Let’s debate this. Do we want to sign up for this or not?’ So without this printing, we wouldn’t have had a nation.”

A Voltron but for Internet freedoms

Over in Foreign Policy, former State Department official Jared Cohen argues that the Biden administration’s upcoming virtual “Summit for Democracy” should include endorsing the creation of a so-called T-12, or a group of a dozen nations with a shared vision for how the connected world should work:

A steering group such as the T-12, which we have proposed to bring together the world’s leading techno-democracies, would fill a critical gap in existing international organizations and provide an informal mechanism for cooperation on everything from supply-chain audits to alignment on digital currency and electronic payments to standards-setting and investment.

[S]uch a steering group could make space for smaller nations with particular expertise to lead—countries such as Finland, Sweden, and Israel, and eventually other critical states such as Taiwan, which the Biden administration invited to the December convening. This year’s summit could endorse the formation of a T-12 and other groupings of techno-democracies; a step in that direction already appears on the horizon with the Biden administration’s proposal for an “Alliance for the Future of the Internet.”

A protest social that actually works

One beneficiary of this summer’s fight between Twitter and the government of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi is a new social network called Koo, Gerry Shih reports in the Washington Post:

In the months since Twitter’s feud with the government, a parade of Indian cabinet ministers, government agencies and right-wing celebrities have opened accounts on Koo to support a homegrown competitor, bringing millions of Indian followers with them. The sudden spike in visibility has brought Koo a $30 million investment round from Tiger Global and Accel, two U.S. venture capital funds that once bet on another young social media start-up: Facebook. Koo grew from 40 employees at the beginning of the year to more than 200; its app has been downloaded 9 million times, mostly in India but increasingly in Nigeria too.

And just for funsies (and your reader-profile file)

The Washington Post has a feature that lets you pull up the front page of the paper from the day you were born. On thing: the paper notes that it’s gonna hang on to that birthdate and add to what it knows about you.